Life Extension Magazine®

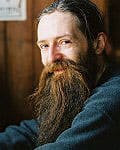

Aubrey de Grey is a biomedical gerontologist based in Cambridge, England. He is editor-in-chief of the academic journal Rejuvenation Research, author of The Mitochondrial Free Radical Theory of Aging (1999) and co-author of Ending Aging (2007). As Chief Science Officer of the SENS Foundation, Aubrey has been interviewed by numerous media sources in the US and Europe, including an in-depth 60 Minutes report titled “The Quest for Immortality.” Aubrey’s research focuses on whether regenerative medicine can thwart the aging process. He works on the development of what he calls “Strategies for Engineered Negligible Senescence” (SENS), a tissue-repair initiative intended to rejuvenate the human body and allow an indefinite life span. To this end, he has identified seven types of molecular and cellular damage caused by normal metabolic processes. Aubrey’s focus is to perfect therapies to repair this damage. We asked Aubrey to write a concise summary of where the SENS Foundation’s research stands now and why more resources are not being allocated to eradicating aging.

Aubrey begins…Historically, the tacit goal of those who dare to dream of postponing age-related ill health has been to apply some kind of intervention to retard pathogenic aging processes. The thinking has been:

However, it has proven challenging up until now to execute this plan. In the past decade, a radically different approach to intervening in aging has emerged. It took a few years to gain credence within the biogerontology community, and there remain some old guard who resist engaging in debate on this topic. Fortunately, the army of prestigious academics who enthusiastically endorse this new approach, at least as a viable alternative to prior ideas, has grown to a point where it is unrealistic to reject it out of hand. This approach is the application of regenerative medicine to aging. Regenerative medicine is the process of creating living, functional tissues to repair or replace cellular function lost due to damage, including injuries sustained as a consequence of aging. Regenerative medicine refers to clinical therapies that may involve the injection of stem cells or progenitor cells; the induction of removal of damaged molecules or cells by biologically active molecules; and transplantation of in vitro grown organs and tissues, all with the goal of restoring the structure of aged tissue to its state in young adulthood. This field holds the promise of regenerating damaged tissues in the body by stimulating previously irreparable organs to heal themselves. SENS Foundation is focused on pursuing this approach, especially by sponsoring the early stage, proof-of-concept research that is required in some areas that are still being neglected by other funding bodies. Details can be found in my academic publications (especially between 2002 and 2007) at www.sens.org and in my book Ending Aging (St. Martin’s Press, 2007). Since aging is indisputably humanity’s worst medical problem, with the treatment (albeit only minimally effective) of age-related diseases consuming the vast majority of the industrialized world’s medical budget, one would imagine that all reasonable approaches to the development of medicine to postpone it would be vigorously pursued and well funded. Unfortunately, none of them are. Neither the retardation of aging nor its repair receives a fraction of the research budget—whether from the public purse or from the for-profit biotech sector—that is enjoyed by disease-specific research. And this is despite the fact that gerontologists have been pointing out for decades that even modest progress in the implementation of “preventative geriatrics”—which is exactly what treatment for aging would be—would be staggeringly cost-effective. Why so little money is being allocatedI believe that the overwhelming reason why politicians (and, to a lesser extent, companies) have not heard this message is not because they fail to understand it but because they dispute the premise. There is a profoundly deep-seated belief that aging is untreatable. This has been reinforced, I am afraid to say, by the short-sighted protestations of past gerontologists who mistakenly claimed “aging is not a disease.” These grossly inaccurate proclamations also reinforce their audience’s tragic misconception as to whether aging is in fact a bad thing at all! Thus, as long as mainstream gerontologists can point only to very flimsy evidence that anything substantive could be expected to emerge from their efforts even if greatly increased funding were forthcoming, they will fail to provide a convincing argument that vastly greater sums of resources should be allocated to this critical arena of medical research. It doesn’t matter how good a case we make that astronomically many dollars will be saved by progress against aging at a relatively small cost in the funding of the necessary research. As long as the holders of purse strings continue to believe that there is no chance whatsoever of research delivering progress against aging, they will conclude that such research is quixotic, so the necessary resources will not be mobilized. This brings me to the first opportunity that arises from the new paradigm of applying regenerative medicine to aging. Regenerative medicine has not enjoyed a precisely smooth progression from concept to clinic over the years, but today it is riding high. Breakthroughs in stem cell research (most notably the “induced pluripotent stem cell” approach to the immune rejection problem) and in tissue engineering (most notably the decellularization approach to the vascularization problem) has propelled regenerative medicine to an enviable stature within biology and biotechnology, among both the scientific community and the general public. Most importantly, this stature exists in terms of the approach’s perceived feasibility, not merely its theoretical attractiveness. Accordingly, to the extent that its applicability to aging is accepted, regenerative medicine has the potential to transcend the entrenched fatalism that I have noted above. Will translational gerontology be accepted by aging researchers?It remains, therefore, to examine the question of whether the applicability of regenerative medicine to aging will be accepted. The effort to elevate it to that status is, I must concede, a work in progress. The core difficulty is that, in order to appreciate the feasibility of repairing the molecular and cellular damage of aging, one must acquire an in-depth grasp of two fields that have historically communicated hardly at all. Regenerative medicine has overwhelmingly been developed with a view to treating acute injury, so very few of its practitioners are up to speed on the current status of biogerontology. Conversely, the focus of biogerontology on comparative analysis, with the aim of eventually developing interventions that slow aging rather than repairing it, has not induced biogerontologists to maintain a thorough understanding of the rate of progress in regenerative medicine.

Inevitably, this lack of mutual education between the two fields has resulted in a high degree of over-pessimism about each other’s work: being out-of-date about a field equates inexorably to presuming that it is less far advanced than it actually is. My own work over the past several years has, accordingly, incorporated a sustained effort to bring these communities together and facilitate that mutual education. Unfortunately, there is an extremely powerful force opposing this ostensibly uncontroversial effort: funding. As science funding has fallen further and further short of demand, and investigators have been forced to spend ever more of their time applying for grants and publishing as much as possible to increase their chances of said funding, it has become progressively less possible to pursue interdisciplinary work, and more imperative to “stick to what one knows” and get money in the door by playing to one’s established strengths. This is immensely bad for science in general, as is probably obvious to readers. But it is particularly bad in the case of biogerontology. This is because, among scientific disciplines, biogerontology has a very—in fact, arguably a uniquely—high profile in the mainstream media. The problem is that the “newcomer” nature of regenerative medicine on the biomedical gerontology playing field translates into considerable unfamiliarity with its relevance to aging on the part of journalists. It remains the unfortunate case that when a reporter reaches for his or her phone book in relation to some new breakthrough concerning aging, the recipients of the calls are overwhelmingly those who represent the old-school, “retardation” approach to combating aging. This might not be so problematic if scientists were mainly minded to highlight the importance of diversity in approaching any research area, but the funding-fuelled tyranny described above decisively prevents such altruism. The result is that the public, policy-makers, and most of the scientific community are maintained in a state of wholly inadequate information on this topic. The benefit to those who are already able to helpBiogerontology is not your average scientific discipline. It is the study of a phenomenon that currently accounts for two-thirds of all deaths worldwide, and 90% of all deaths within the industrialized world. If measured in terms of suffering or of health care costs, the numbers are equally staggering. As several of my colleagues have noted over many decades, and with increasing energy since the turn of the millennium, the impact of even a modest degree of progress in postponing age-related diseases, as a result of intervening in their common cause (aging), would be immense. The missing link, as already discussed, is the view of policy-makers as to whether there is any chance of success. This could be changed if those to whom policy-makers look for guidance were to alert them to the potential for regenerative medicine to postpone aging, but, as I have also discussed above, the funding environment within which the acknowledged experts of biogerontology are forced to work impels them to ignore that option, whether in their own work or in their pronouncements to others, in favor of the far less promising alternatives that they have pursued in years past.

So why is everyone still oblivious to this disaster? Ultimately, I believe that the answer comes down to just one thing: a failure to appreciate who can potentially benefit from progress. The massive Achilles’ heel of biomedical gerontology in terms of appeal to the wider world has always been its focus on lifelong interventions. Those in a position to influence the level of financial support for such work, therefore, are required to start from a position of disenfranchised altruism (since they are already too old to benefit from therapies that need to be begun in youth or earlier). That is a noble position, to be sure, but realistically it is not one that enjoys prolific favor from the public. In particular, it is not a promising target for philanthropy. But the regenerative approach changes all that—indeed, it abolishes it. The whole point of all regenerative medicine is to start with people who are already carrying a significant quantity of damage, which the intervention will then repair. As such, if it can be made to work, rejuvenation biotechnology has the capacity to deliver the substantial (exactly how substantial remains to be seen, but we won’t know until we try) postponement of all the debilities that we most fear as we progress toward the age at which we expect our health to fail. And it can deliver it to people who are already in middle age or older by the time the therapies materialize. Turning research into realitySo, well, can it be made to work? There are two ways for those with the financial resources (i.e., today’s ultra-wealthy) to answer that question. One way is to accept the prognostications of those who occupy positions of prestige among the established biogerontology community, who still know and understand little of regenerative medicine, and who, with varying degrees of stridency, declare that aging is practically beyond the reach of medicine and that all we can realistically seek to do is understand aging well enough to postpone the ill-health of old age by a few years. The other way is to enlighten those with financial resources to the burgeoning field of regenerative medicine and the ever-increasing plethora of distinguished leaders of that field who are lining up behind the proposition that aging can be reversed by the comprehensive repair of the molecular and cellular damage that underlies it. If these individuals want to avoid the ill health of old age, now is their chance to take meaningful action. We still need as much knowledge as we can get about how aging really works. But augment it with a similar level of support for unashamedly translational biogerontology, focused on the postponement of age-related ill health, and focused especially on interventions that will benefit those who are already adversely impacted by aging, and the result will be the saving of hundreds of millions of lives, along with countless life-years of suffering. We are all in the same lifeboat. The difference is that some have available financial resources that could result in their own rescue from the horrific consequences of aging, along with all of mankind. I urge those fortunate enough to have accumulated wealth beyond their worldly needs to emulate what Larry Ellison has done, i.e., support scientists who are aggressively researching means to gain control over aging. It seems so logical, yet Larry Ellison is among only a few who has demonstrated the clear vision to fund those who could enable humans to rapidly evolve into a species that enjoys an indefinitely extended healthy life span. The next section of this article describes Larry Ellison’s unique approach to funding aging research. I urge Larry and others to consider augmenting their translational biogerontology arena, and particularly to the regenerative medicine approach. |

Larry Ellison is a speculator. He is also a visionary. Not afraid of risk or ridicule, this maverick mogul of Silicon Valley built his Oracle software empire (and his $39.5 billion net worth) with less than $2,000 in savings on a philosophy that dismisses convention; and it is exactly that philosophy that he is betting on to change the face of aging and age-related diseases. Some may know him for his high-dollar, daredevil lifestyle, like owning the fastest sailboat in history and racing it and leading Team Oracle to a 2010 World Cup victory, flying his Italian F-16 fighter jet for fun, or owning the largest private yacht in the world. But few will know he has a serious philanthropic side that is just as focused as his business acumen. The Ellison Medical Foundation is the largest private funder of research on aging and the second largest overall funder—second only to the federal government’s National Institute on Aging. Since its inception in 1998, Ellison’s Medical Foundation has provided more than $300 million to fund basic biomedical research on aging relevant to understanding life span development processes and age-related diseases and disabilities, including stem cells, telomeres, longevity genes, DNA and mitochondrial damage, Werner Syndrome, Alzheimer’s disease, neural development, degeneration and cognitive decline, and cellular response systems to aging and toxins. It is said the research foundation began not so much from altruistic origins but from the confluence of Ellison’s interest in science and an aversion to mortality. Cancer killed Ellison’s adoptive mother when he was in college and Oracle co-founder Robert Miner in 1994. A chance encounter with an equally visionary scientist, the late Nobel laureate Dr. Joshua Lederberg, led Larry Ellison to understanding the therapeutic and market potential of biotechnology. After hearing Lederberg, an icon of molecular biology and artificial intelligence, speak on the topic at a Stanford University symposium in 1990, Ellison was so intrigued by the scientist that he invited him to his home for a weekend. That weekend turned into a lifelong friendship. In 1994, Lederberg returned the favor with an invitation to vacation with him for two weeks—in the lab. Never one to pass up a challenge, Ellison took Lederberg up on the offer, likely to explore his own interests in molecular biology and science. During those 14 days, pushed by his own interest to challenge himself, Ellison starting asking questions that altered the course of Lederberg’s experiments and would change the face of aging research in this country for years to come. Thus, over the next several years, the beginnings and mission of The Ellison Medical Foundation focused on aging emerged. Lederberg, who was then president emeritus of Rockefeller University, was tapped as director of the Scientific Advisory Board, and Dr. Richard Sprott became the new Foundation’s executive director, after years directing the National Institute of Aging’s Biology of Aging Program. “One of the problems with philanthropy is that people think that once they’ve written the check they’re done,” noted Ellison when asked about his charitable activities. “I believe that in order to be a successful philanthropist, you not only have to write the check but you have to spend enough time with these projects to make sure you are getting results.” And for Ellison, the road to results is often the one least traveled by others. Not surprisingly, The Ellison Medical Foundation’s approach is different, innovative, and bold. As Lederberg once put it, “Our job is to fund the new, the unconventional, and to take chances that others won’t. Our only criterion will be the best science and the best of scientists.” Cutting-edge Aging Research still UnderfundedFifteen years later, The Ellison Medical Foundation continues to “fund people, not projects,” according to Sprott, looking for scientists with track records of creative, productive work and unique ideas, while favoring basic research that may be too risky or speculative to attract mainstream funding. This year, The Ellison Medical Foundation will award a total of $40 million to 25 Senior Scholars and 25 New Scholars, each for four years. “At the moment, that means that at any point in time we are funding 200 laboratories,” says Sprott. And the funding levels are significant. Senior Scholars are awarded about $1 million for 4 years of research, according to Sprott. New Scholars receive approximately $400,000 for four years of research. “My reason for coming here could be summed up with the notion that basic biologic research on aging was the least well-funded research at the National Institute on Aging,” says Sprott. “And it still is.” While all of the degenerative and proliferative diseases of aging are related to basic biological, genetic and molecular processes, “no Congressman believes that he or she or his constituents die of basic biology—they die of diseases,” says Sprott. “And so it doesn’t sound very sexy. It is very hard to attract research dollars for basic biology,” Sprott frustratingly notes. “Even in the view of Josh and Larry and the advisory board, the only long-term solution to age-related problems is to prevent them. And you can only do that with basic biological research. Anything else you do is playing catch up. Unfortunately, most of the money is going to fixing diseases that are already in place. So The Ellison Medical Foundation particularly wishes to stimulate new, creative research that might not be funded by traditional sources or that is often under-funded in the US,” says Sprott. And despite his personal losses from cancer, there are no specific diseases that motivate Ellison or drive The Ellison Medical Foundation’s work, according to Sprott. Ellison is so devoted to basic aging research that the foundation started to focus exclusively on identifying and funding research opportunities that could lead to “quantum leaps” or “paradigm shifts” in scientific understanding that greatly impact human health. “Larry is one of those people who truly understands the need for basic science, and he clearly understands the need for focus. We focus very sharply,” says Sprott. “If we funded a broader variety of things, we would have much less impact on any of them. And I think he appreciates that’s the way you really get something done.” |

The EMF fills a gap, Advances ScienceSuch sentiments are echoed by veteran researcher and EMF Senior Scientist Scholar Dr. Judith Campisi. The current research climate “is the worst I have ever seen it,” says Campisi. “And it is particularly bad for basic aging research right now, as opposed to other aspects of aging research, and certainly as opposed to other fields,” notes Campisi. “It is really terrible right now. And what I think Ellison has done is helping to fill a gap that is a real need.” Campisi, who is a professor and has her own lab at the Buck Institute for Research on Aging in Berkeley, California, knows first-hand the difficulties of securing research funding from the standard government sources like the National Institutes of Health (NIH), including onerous application procedures and extensive oversight once funded. “The Ellison Medical Foundation, I believe, has striven to break the NIH mode of requiring extensive preliminary data and really encourages people to even go outside their fields or to bring people who have not worked in aging to begin to apply what they know in other fields to the problem of aging,” says Campisi, who studies the relationship between cancer and aging. “And in my opinion they have been very successful in doing that.” This is exactly what Ellison and Sprott want to hear. “What we think we can do that is not necessarily done very well by NIH is that we can take a chance on an investigator based on what we know about them in their application or what we know about them from their existing research and track record,” Sprott explains. “If they have a really good idea, we can take a risk because we are not doing it with taxpayer dollars.” Campisi is a perfect example of this. “Cancer is very different than most other age-related diseases,” says Campisi. “Most age-related diseases are degenerative. Your kidneys stop working well, your heart doesn’t work well, your brain stops working well. But cancer is very different,” she says. “In order for a lethal tumor to form, cells have to acquire new functions, new phenotypes, and so we’ve been thinking for years about whether this is coincidence that cancer goes up with age and all these degenerative pathologies go up with age or whether there is real biology that connects them.” Enter TelomeresTelomeres are small units of DNA at the end of our chromosomes. As our cells divide, telomeres progressively shorten until they become dysfunctional, causing aging and age-related diseases, including cancer. But if telomeres can remain intact, they protect the genes inside the cell. Still, while Campisi knew about new theories surrounding telomeres at the time, she had never done research in them. The funding from The Ellison Medical Foundation allowed her to blend her cancer research with telomere research. “At the time I got my Ellison funding, the major paradigm for understanding this potential link was this idea that telomeres, these structures that cap the ends of chromosomes, get shorter with each cell division. And they also get shorter with age. And when they fail, when they get so short that the telomeres fail to function, the cells become senescent. But when cells become senescent, they change their function so much that they can begin to alter the tissue and cause degenerative changes,” says Campisi. “But I had never worked in telomeres. I was just dabbling. “So the link between telomeres and degenerative changes was extremely obscure. And it was through The Ellison Medical Foundation that we were able to do some really interesting molecular studies and sort of close that loop to help us understand how it is that telomere failure related to all of the other inducers of senescence and then how senescent cells can change the tissue-marker environment.” The Ellison Medical Foundation’s funding, Campisi says, was a crucial link that really allowed her and her lab to go outside the box of traditional NIH funding. “It was something we had suspected for many years, and now we have proof, but at the time we only had a suspicion.” While Campisi is no longer funded by The Ellison Medical Foundation, those advancements have allowed her to continue to make “enormous progress.” Not only has she been able to confirm many of the early, very speculative ideas about how senescence might link to degenerative diseases of aging with cancer, but she also has recently been able to identify that senescent cells may be responsible for chronic inflammation in the body. “Very often aged tissues are said to have ‘sterile’ inflammation, meaning a pathologist will look at that tissue and see low-level, chronic inflammation, but there is no evidence of a pathogen. It has nothing to do with infection,” says Campisi. “But we now know that senescent cells have the capability to create that kind of environment,” based in part on an evolutionary need, Campisi believes, for the compromised cell to communicate with the immune system to clear the cell. “But if that damaged cell doesn’t go away, it becomes a chronic situation and we think this is a major reason why senescent cells might drive multiple pathologies, because every major pathology associated with aging has a component, either a cause or an exacerbating factor we now refer to as chronic inflammation.” Basic Research means Saving LivesWith this type of knowledge, scientists and researching physicians affiliated with groups like The Ellison Medical Foundation and Life Extension Foundation® are able to do much more to extend our healthy life spans and prevent needless deaths. The Ellison Medical Foundation has also funded major initiatives in longevity genes and life span extension. In 2000, Dr. Nir Barzilai at Albert Einstein College of Medicine of Yeshiva University also became a Senior Scholar in Aging. His research focused on identifying longevity genes and biological factors associated with long life span in humans based on Ashkenazi Jews and Old Order Amish populations. He found that both groups had significantly larger high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) particle sizes than control groups.

As many Life Extension readers may already know, in terms of cardiovascular health, this characteristic is associated with lower prevalence of hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic syndrome. Dr. Barzilai’s research identified two genetic alleles seen with increased frequency in the centenarians and their offspring. His research even found that one of the genetic mutations also conferred better cognitive function in the centenarians. “What we’re doing is investing philanthropic dollars in basic research that has the potential to have a very large impact on everyone’s lives,” notes Sprott. “When you look at the website and look at the projects we fund, you see a lot about life span extension. But we don’t fund them for precisely that reason. We fund them to understand the basic processes so that we can improve the quality of the latter part of the life span. So we are more interested in quality rather than quantity,” notes Sprott. “And our underlying theme is that if we can eliminate the diseases that are age-related that will translate into a big effect for people’s lives.” What’s the Future of Aging Research?Going forward, Sprott’s goal for The Ellison Medical Foundation is to “stay on top of what is cutting edge research at any point in time and make sure that we are leading and providing the funds for those cutting edge scientists to get far enough down the road that they are successful for funding from more traditional sources.” And come late summer and early fall, Ellison, Sprott and the foundation’s Scientific Advisory Board will have funded a new round of New and Senior Scientists. Still, The Ellison Medical Foundation only funds a researcher once, which means there is still a tremendous unmet need in aging research. “We have a firm policy that no one gets a second award,” Sprott says flatly. “When we first started out, we thought we would run out of bright people fairly fast. But in fact, we get more and more good applications every year. We have been at this 14 years and we are finding more and more really good people. But if we give people second awards—we’ve funded 800 so far—there would be another 800 people standing in line looking for an award. And we wouldn’t fund anybody new.” ConclusionLarry Ellison and David Murdock (described below) are examples of what ultra-wealthy individuals should be doing to fund research aimed at eliminating the horrific consequences of aging and its associated pathologies. They are not the only philanthropists supporting aging research, but they remain in the tiny minority. Unlike any other philanthropy, the fruits of aging research benefit virtually every human on the planet. Even if one were to find a cure for all cancers, this would only benefit those stricken with cancer. Aging, on the other hand, strikes every human who lives long enough. Based on what you are learning in this month’s issue of Life Extension Magazine®, scientists are discovering enough about the mechanisms of aging to make significant strides…but only if enough research dollars are intelligently allocated to perfect methods to control and reverse it. To learn about a new initiative to accelerate the pace of aging-reversal research, visit "New Initiative to Accelerate Anti-Aging Research". If you have any questions on the scientific content of this article, please call a Life Extension® Health Advisor at

|