Life Extension Magazine®

The long, dark days of another winter have come and gone. Tens of millions of Americans would be surprised to learn that winter has left them deficient in vitamin D. Your chances of being one of them are probably much greater than you imagine. Vitamin D is synthesized in the skin in response to sunlight exposure, but few people achieve optimal levels this way, in part due to the limited ultraviolet light available during the winter months. This seasonal deficit is compounded by the fact that many people avoid sun exposure during the spring and summer months because of concern about premature skin aging and cancers like melanoma. Alarming new research suggests that these factors are contributing to a year-round epidemic of vitamin D deficiency, particularly in elderly adults. Vitamin D does far more than promote healthy teeth and bones. Its role in supporting immunity, modulating inflammation, and preventing cancer make the consequences of vitamin D deficiency potentially devastating. A growing number of scientists who study vitamin D levels in human populations now recommend annual blood tests to check vitamin D status. In this article, we examine the factors that contribute to the widespread prevalence of vitamin D deficiency, the latest studies supporting vitamin D’s critical role in preventing disease, and how much supplemental vitamin D you need to achieve optimal blood levels. Vitamin D Deficiency: An Overlooked EpidemicVitamin D is a fat-soluble prohormone—that is, it has no hormone activity itself, but is converted to a molecule that does, through a tightly regulated synthesis mechanism. Its two major forms are vitamin D2 (or ergocalciferol) and vitamin D3 (or cholecalciferol). Vitamin D also refers to metabolites and other analogues of these substances. Vitamin D3 is produced in skin exposed to sunlight, specifically ultraviolet B radiation. While vitamin D is best known for promoting calcium absorption and bone health, researchers have recently discovered important new roles for this versatile vitamin.1 As an active hormone,2 vitamin D is now seen as playing a central role in controlling immunity and inflammation,1,3,4 two vital processes that are tied to a host of age-related disease conditions.5-10 Just as scientists are discovering critical new roles for vitamin D, they are also finding that shockingly few people have blood levels of vitamin D adequate to support their daily needs.5,6 One leading researcher has referred to this deficit as a “vitamin D epidemic.”7 Estimates of the percentage of US adolescents and adults who are vitamin D deficient range from 21% to 58%,11 while as many as 54% of homebound older adults are believed to be vitamin D deficient.12 Because vitamin D3 is obtained in humans primarily as a result of exposure to sunlight,8 this puts people living outside the tropics at particular risk for vitamin D deficiency, especially from late fall to early spring.9 Further compounding the problem, many public health officials are concerned that their warnings about avoiding the sun because of skin cancer risk may in fact be causing people to limit their sun exposure to an unhealthy extent.10,13 Because sun exposure does pose significant health risks, and most Americans live outside of the regions where they can get adequate sun in winter, perhaps the best way to address this dilemma is by paying close attention to your blood levels of vitamin D and optimizing them through appropriate supplementation. Life Extension recommends that adults check their blood levels and supplement with enough vitamin D3 to achieve optimal blood levels.6-8 To meet all of the body’s needs for proper vitamin D activity, many scientists now advocate supplementing with doses that are considerably higher than the minimums currently recommended by the Institute of Medicine.14 While vitamin D can be obtained through a few dietary sources such as fish, eggs, and dairy products, these foods fail to provide the daily levels required by most individuals, thus necessitating vitamin D supplementation.

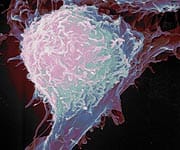

Applications for Preventing and Treating CancerStrong epidemiological data now implicate low vitamin D levels in at least 16 different malignancies.47 Powerful clinical evidence indicates that vitamin D may be useful in preventing and even treating colon and prostate cancers, while suggestive evidence points to its effects in countering lung, breast, skin, and other cancers.16,47

Colon CancerTwenty-five years of research suggests that detecting and correcting vitamin D deficiency may be especially important in averting colon cancer, a disease that claims approximately 56,000 lives each year in the United States.48 An early study of 1,954 men found that those with the lowest vitamin D intake had more than double the risk of colon cancer compared to men with the highest intake.49 Colon cells reproduce very quickly, placing them at risk for becoming malignant. When active vitamin D was applied to colon cells in culture, reproduction rates fell by 57% in normal colon tissue and by 52% in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis, an inherited syndrome characterized by many pre-cancerous polyps.50 In a laboratory study, pretreatment with vitamin D made colon cancer cells easier to kill with hydrogen peroxide and other natural oxidants present in the bowel.51 A large randomized trial from 2003 helped to establish a clinical role for vitamin D in preventing colon cancer.52 Eight hundred three subjects with previous colorectal adenomas (which can lead to cancer if they recur) were given calcium supplements or placebo, and their rates of adenoma recurrence were measured. Calcium supplements reduced the risk of adenoma recurrence by 29% in subjects with normal D levels. This study demonstrated that both calcium and adequate vitamin D levels are needed to reduce colon cancer risk. In a 2006 study,53 researchers surgically divided individual adenomatous (potentially precancerous) polyps, removing approximately 50% from 19 patients. They marked the remnants of the polyps in the intestine so they could identify them later, and studied cell proliferation in the polyp tissue before and after six months of treatment with oral vitamin D3 (400 IU) and calcium carbonate (1500 mg, three times daily) or placebo. Adenomas from patients treated with calcium and vitamin D3 showed marked declines in cell proliferation and other signs of cancerous change, while there was no change in tissue taken from the control patients.

Cancer prevention specialists at the University of California recently conducted an extensive review of scientific papers published worldwide between 1966 and 2004. Their analysis suggested that taking 1000 international units (IU) of vitamin D3 daily lowers an individual’s risk of developing colorectal cancer by 50%. The researchers recommended increased intake of vitamin D3 as an inexpensive, non-toxic preventive therapy for colon cancer. Specifically, they hope to see the federal government officially recommend intake of 1000 IU per day of vitamin D3 for cancer prevention.48 | ||||||

Prostate CancerOptimal levels of vitamin D may also help protect prostate health.19,54 Aware that low vitamin D levels are a major risk factor for prostate cancer,40,55,56 researchers examined the vitamin’s preventive effect in a cancer-prone mutant strain of mice.57 Mutant and control mice were given vitamin D for four months either before or after developing the first signs of cancer. Vitamin D substantially reduced the occurrence of early cancerous changes in tissue, yet appeared to have no effect on the androgen (male hormone) system. This is crucial, because many conventional prostate cancer drugs impair androgen function. Human prostate cancer cells in culture show similar reductions in cancerous changes and proliferation when treated with vitamin D3 and a synthetic retinoid (a vitamin A-like compound).58 A 1998 study demonstrated that vitamin D can reduce prostate cancer growth in human subjects. Seven men with recurrent prostate cancer following surgery or radiation (as measured by increasing levels of prostate-specific antigen, or PSA) were given a prescription form of vitamin D called calcitriol (Rocaltrol®) at increasing doses from 0.5 to 2.5 mcg (20-100 IU) per day. The rate of PSA increase (an indicator of disease progression) during treatment fell significantly compared to the rate before treatment in six of the subjects, suggesting a slowing of prostate cancer progression.59 In a related study, weekly dosing with calcitriol (at 20 IU per kilogram of body weight) increased median PSA doubling time in men who had been treated for prostate cancer.60,61 An increased PSA doubling time means that it takes longer for the PSA cancer marker to elevate (double), which is a favorable sign. Treatment of existing prostate cancers with vitamin D also shows promise. In a 2006 Phase II clinical trial,62 researchers administered calcitriol three times weekly (at up to 12 mcg [480 IU] per dose) with the potent steroid dexamethasone. Thirty-seven men with androgen-independent prostate cancer were treated for at least one month. Eight patients had notable decreases in levels of PSA, a marker for tumor size. The researchers concluded that because there was minimal toxicity from this combination, it is a safe and feasible anti-tumor treatment.

Breast and Other CancersAbundant laboratory research demonstrates that vitamin D prevents human breast cancer cell proliferation and enhances the differentiation of cells into normal, healthy tissue.18,21-23,63,64 Powerful evidence also indicates that rates of breast cancer, like those of many other cancers, are lower in populations with greater exposure to sunlight or greater dietary intake of vitamin D.65-67 Similarly, enticing (though not yet clinically proven) evidence suggests a role for vitamin D supplementation in preventing or treating other cancers, including ovarian cancer, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and cancers of the head and neck.20,47,68-70 Many cancer specialists advise checking vitamin D levels at least once a year, and supplementing with vitamin D if a deficiency is detected.6,40 Vitamin D Helps Alleviate Heart FailureHeart failure—the heart’s inability to pump enough blood to meet the body’s requirements—is a leading cause of death in industrialized nations.71 Scientists believe that elevated levels of circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines may contribute to heart failure, and that vitamin D may offer heart-protective benefits by quelling these inflammatory mediators.72

In a recent double-blind clinical trial, 123 patients with congestive heart failure were randomly assigned to receive either vitamin D3 (50 mcg [2000 IU] per day) plus 500 mg of calcium or placebo plus 500 mg of calcium.72 Over the nine months of the study, patients who supplemented with vitamin D had greatly increased levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-10 and lower levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Scientists believe that by reducing the inflammatory environment in congestive heart failure patients, vitamin D3 holds promise as an anti-inflammatory therapeutic for people suffering from heart failure. A 2005 study reported on the use of vitamin D and other nutrients in chronic heart failure.71 In a randomized trial, 28 chronic heart failure patients supplemented with 200 IU of vitamin D, 150 mg of coenzyme Q10, minerals, antioxidants, and B vitamins or placebo for nine months. The supplemented patients had an impressive 17% decrease in the heart’s left ventricular volume, which typically is increased in chronic heart failure and adds to the work required of the already-fatigued heart muscle. By contrast, left ventricular volume increased 10% in the placebo group. Supplemented patients also had a modest increase in quality-of-life scores. These findings indicate that vitamin D supplementation, in combination with coenzyme Q10, vitamins, and minerals, can offer important support for people with chronic heart failure.

| |||||||

Vitamin D May Help Prevent DiabetesExciting research also indicates a possible therapeutic role for vitamin D in preventing diabetes. Vitamin D supplementation may reduce susceptibility to type II diabetes by slowing the loss of insulin sensitivity in people who show early signs of the disease. Researchers studied 314 adults without diabetes and gave them either 700 IU of vitamin D and 500 mg of calcium daily or a placebo for three years.73 Among subjects who had impaired (slightly elevated) fasting glucose levels at the study’s onset, those taking the active supplement had a smaller rise in glucose levels over three years than did the controls, as well as a smaller increase in insulin resistance. The researchers concluded that for older adults with impaired glucose levels, supplementing with vitamin D and calcium may help avert metabolic syndrome and type II diabetes. Type I (insulin-dependent) diabetes is an autoimmune condition, in which the body’s immune system attacks its own insulin-producing pancreatic beta cells. Low vitamin D levels are associated with the development of autoimmune conditions,40,74,75 including type I diabetes,38 and scientists have proposed that vitamin D supplementation may help prevent the disease.76 A very large population-based study in Europe demonstrated the powerful effect of vitamin D supplementation in protecting children against the development of type I diabetes.77 Data from 820 diabetics and 2,335 non-diabetic controls showed that children who received vitamin D supplements in infancy reduced their risk of developing type I diabetes by approximately 33%. The researchers believe that activated vitamin D may protect growing children from autoimmune attack on insulin-producing cells of the pancreas.

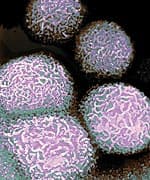

Vitamin D Provides Essential Immune SupportVitamin D appears to be essential in maintaining healthy white blood cells and a robust immune system.75 A recent paper presented persuasive evidence that seasonal infections such as influenza may actually be the result of decreased vitamin D levels,26 not of increased wintertime viral activity, which has been the longstanding conventional wisdom.78 This makes sense, because vitamin D receptors are present on many of the immune system cells responsible for killing viruses and deadly bacteria, and the vitamin—which is less environmentally available in the winter—appears to be a requirement for proper activation of these cells.79,80 A randomized, double-blind study published in 2006 found that vitamin D may support recovery from tuberculosis, a common and deadly infection that most commonly affects the lungs. When patients with moderately advanced tuberculosis supplemented with 0.25 mg (10,000 IU) per day of vitamin D for one week, they had significantly higher rates of improvement than patients who received a placebo.81 Kidney dialysis patients often demonstrate decreased vitamin D levels as well as impaired cellular immune response. Dialysis patients with decreased vitamin D levels and impaired function of anti-viral and anti-cancer natural killer cells experienced substantial increases in natural-killer-cell activity after just one month of supplementation with prescription vitamin D (calcitriol) at 0.5 mcg (20 IU) per day.27 In the laboratory, the same researchers demonstrated that vitamin D treatment of “generalized” white blood cells called monocytes caused them to mature into active natural killer cells within 24 hours.

Further evidence of vitamin D’s ability to bolster protective immune function comes from a laboratory study published earlier this year.82 Researchers discovered that skin cells responding to injury require vitamin D3 to “switch on” vital proteins involved in recognizing and responding to the microbes that cause wound infections. This finding has tremendous implications for preventing and treating wound infections. ConclusionEven in people who take vitamin D supplements, the percentage of those with sub-optimal levels remains surprisingly high. Humans cannot arbitrarily consume massive doses of vitamin D (unlike water-soluble nutrients such as vitamin C). For this nutrient, individualized dosing is of particular importance, and the only way to accomplish this is through vitamin D blood testing. With deficiencies likely to be most pronounced following the long winter months, spring is an excellent time to investigate your own vitamin D status. Detecting deficient levels allows you and your physician to implement vitamin D supplementation to help avert illnesses associated with inadequate vitamin D levels. Optimizing your vitamin D intake may be a safe, low-cost way to protect against cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, immune disorders, and depression, among other serious health conditions.

| ||||||

| References | ||||||

| 1. Nagpal S, Na S, Rathnachalam R. Noncalcemic actions of vitamin D receptor ligands. Endocr Rev. 2005 Aug;26(5):662-87. 2. Dukas L, Staehelin HB, Schacht E, Bischoff HA. Better functional mobility in community-dwelling elderly is related to D-hormone serum levels and to daily calcium intake. J Nutr Health Aging. 2005 Sep;9(5):347-51. 3. May E, Asadullah K, Zugel U. Immunoregulation through 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and its analogs. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy. 2004 Dec;3(4):377-93. 4. van EE, Mathieu C. Immunoregulation by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3: basic concepts. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2005 Oct;97(1-2):93-101. 5. Guillemant J, Le HT, Maria A, et al. Wintertime vitamin D deficiency in male adolescents: effect on parathyroid function and response to vitamin D3 supplements. Osteoporos Int. 2001;12(10):875-9. 6. Holick MF. Sunlight and vitamin D for bone health and prevention of autoimmune diseases, cancers, and cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004 Dec;80(6 Suppl):1678S-88S. 7. Holick MF. The vitamin D epidemic and its health consequences. J Nutr. 2005 Nov;135(11):2739S-48S. 8. Nowson CA, Margerison C. Vitamin D intake and vitamin D status of Australians. Med J Aust. 2002 Aug 5;177(3):149-52. 9. Brot C, Vestergaard P, Kolthoff N, et al. Vitamin D status and its adequacy in healthy Danish perimenopausal women: relationships to dietary intake, sun exposure and serum parathyroid hormone. Br J Nutr. 2001 Aug;86 Suppl 1S97-103. 10. Lucas RM, Repacholi MH, McMichael AJ. Is the current public health message on UV exposure correct? Bull World Health Organ. 2006 Jun;84(6):485-91. 11. Looker AC, Dawson-Hughes B, Calvo MS, Gunter EW, Sahyoun NR. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D status of adolescents and adults in two seasonal subpopulations from NHANES III. Bone. 2002 May;30(5):771-7. 12. Gloth FM 3d, Gundberg CM, Hollis BW, Haddad JG Jr, Tobin JD. Vitamin D deficiency in homebound elderly persons. JAMA. 1995 Dec 6;274(21):1683-6. 13. Berwick M, Armstrong BK, Ben-Porat L, et al. Sun exposure and mortality from melanoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005 Feb 2;97(3):195-9. 14. Vieth R. Vitamin D supplementation, 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations, and safety. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999 May;69(5):842-56. 15. Chel VG, Ooms ME, Popp-Snijders C, et al. Ultraviolet irradiation corrects vitamin D deficiency and suppresses secondary hyperparathyroidism in the elderly. J Bone Miner Res. 1998 Aug;13(8):1238-42. 16. Trump DL, Muindi J, Fakih M, Yu WD, Johnson CS. Vitamin D compounds: clinical development as cancer therapy and prevention agents. Anticancer Res. 2006 Jul;26(4A):2551-6. 17. Dusso AS, Brown AJ, Slatopolsky E. Vitamin D. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005 Jul;289(1):F8-28. 18. Jensen SS, Madsen MW, Lukas J, Binderup L, Bartek J. Inhibitory effects of 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) on the G(1)-S phase-controlling machinery. Mol Endocrinol. 2001 Aug;15(8):1370-80. 19. Krishnan AV, Moreno J, Nonn L, et al. Novel pathways that contribute to the anti-proliferative and chemopreventive activities of calcitriol in prostate cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007 Jan 15. 20. Gedlicka C, Hager G, Weissenbock M, et al. 1,25(OH)2Vitamin D3 induces elevated expression of the cell cycle inhibitor p18 in a squamous cell carcinoma cell line of the head and neck. J Oral Pathol Med. 2006 Sep;35(8):472-8. 21. Lowe L, Hansen CM, Senaratne S, Colston KW. Mechanisms implicated in the growth regulatory effects of vitamin D compounds in breast cancer cells. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2003;164:99-110. 22. Swami S, Raghavachari N, Muller UR, Bao YP, Feldman D. Vitamin D growth inhibition of breast cancer cells: gene expression patterns assessed by cDNA microarray. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003 Jul;80(1):49-62. 23. Colston KW, Hansen CM. Mechanisms implicated in the growth regulatory effects of vitamin D in breast cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2002 Mar;9(1):45-59. 24. Yee YK, Chintalacharuvu SR, Lu J, Nagpal S. Vitamin D receptor modulators for inflammation and cancer. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2005 Aug;5(8):761-78. 25. Vojinovic S, Vojinovic J, Cosic V, Savic V. Effects of alfacalcidol therapy on serum cytokine levels in patients with multiple sclerosis. Srp Arh Celok Lek. 2005 Dec;133 Suppl 2:124-8. 26. Cannell JJ, Vieth R, Umhau J,C et al. Epidemic influenza and vitamin D. Epidemiol Infect. 2006 Dec;134(6):1129-40. 27. Quesada JM, Serrano I, Borrego F, et al. Calcitriol effect on natural killer cells from hemodialyzed and normal subjects. Calcif Tissue Int. 1995 Feb;56(2):113-7. 28. Amento EP. Vitamin D and the immune system. Steroids. 1987 Jan;49(1-3):55-72. 29. Regan E, Flannelly J, Bowler R, et al. Extracellular superoxide dismutase and oxidant damage in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005 Nov;52(11):3479-91. 30. Henrotin Y, by-Dupont G, Deby C, Franchimont P, Emerit I. Active oxygen species, articular inflammation and cartilage damage. EXS. 1992;62:308-22. 31. Black PN, Scragg R. Relationship between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin d and pulmonary function in the third national health and nutrition examination survey. Chest. 2005 Dec;128(6):3792-8. 32. Wright RJ. Make no bones about it: increasing epidemiologic evidence links vitamin D to pulmonary function and COPD. Chest. 2005 Dec;128(6):3781-3. 33. Brody JS, Spira A. State of the art. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, inflammation, and lung cancer. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006 Aug;3(6):535-7. 34. Sanz J, Moreno PR, Fuster V. Update on advances in atherothrombosis. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2007 Feb;4(2):78-89. 35. de Ferranti SD, Rifai N. C-reactive protein: a nontraditional serum marker of cardiovascular risk. Cardiovasc Pathol.2007 Jan;16(1):14-21. 36. Despres JP, Lemieux I. Abdominal obesity and metabolic syndrome. Nature. 2006 Dec 14;444(7121):881-7. 37. Guzik TJ, Mangalat D, Korbut R. Adipocytokines - novel link between inflammation and vascular function? J Physiol Pharmacol. 2006 Dec;57(4):505-28. 38. Akerblom HK, Vaarala O, Hyoty H, Ilonen J, Knip M. Environmental factors in the etiology of type 1 diabetes. Am J Med Genet. 2002 May 30;115(1):18-29. 39. Cutolo M, Otsa K, Laas K, et al. Circannual vitamin d serum levels and disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis: Northern versus Southern Europe. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2006 Nov;24(6):702-4. 40. Grant WB. Epidemiology of disease risks in relation to vitamin D insufficiency. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2006 Sep;92(1):65-79. 41. Chiu KC, Chu A, Go VL, Saad MF. Hypovitaminosis D is associated with insulin resistance and beta cell dysfunction. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004 May;79(5):820-5. 42. Martini LA, Wood RJ. Vitamin D status and the metabolic syndrome. Nutr Rev. 2006 Nov;64(11):479-86. 43. Boucher BJ. Inadequate vitamin D status: does it contribute to the disorders comprising syndrome ‘X’? Br J Nutr. 1998 Apr;79(4):315-27. 44. Achinger SG, Ayus JC. The role of vitamin D in left ventricular hypertrophy and cardiac function. Kidney Int Suppl. 2005 Jun;(95):S37-S42. 45. Dietrich T, Nunn M, wson-Hughes B, Bischoff-Ferrari HA. Association between serum concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and gingival inflammation. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005 Sep;82(3):575-80. 46. Levin A, Li YC. Vitamin D and its analogues: do they protect against cardiovascular disease in patients with kidney disease? Kidney Int. 2005 Nov;68(5):1973-81. 47. Grant WB, Strange RC, Garland CF. Sunshine is good medicine. The health benefits of ultraviolet-B induced vitamin D production. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2003 Apr;2(2):86-98. 48. Gorham ED, Garland CF, Garland FC, et al. Vitamin D and prevention of colorectal cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2005 Oct;97(1-2):179-94. 49. Garland C, Shekelle RB, Barrett-Connor E, et al. Dietary vitamin D and calcium and risk of colorectal cancer: a 19-year prospective study in men. Lancet. 1985 Feb 9;1(8424):307-9. 50. Thomas MG. Luminal and humoral influences on human rectal epithelial cytokinetics. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1995 Mar;77(2):85-9. 51. Koren R, Wacksberg S, Weitsman GE, Ravid A. Calcitriol sensitizes colon cancer cells to H2O2-induced cytotoxicity while inhibiting caspase activation. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2006 Oct;101(2-3):151-60. 52. Grau MV, Baron JA, Sandler RS, et al. Vitamin D, calcium supplementation, and colorectal adenomas: results of a randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003 Dec 3;95(23):1765-71. 53. Holt PR, Bresalier RS, Ma CK, et al. Calcium plus vitamin D alters preneoplastic features of colorectal adenomas and rectal mucosa. Cancer. 2006 Jan 15;106(2):287-96. 54. Brawley OW. The potential for prostate cancer chemoprevention. Rev Urol. 2002;4 Suppl 5S11-7. 55. Grant WB. An estimate of premature cancer mortality in the U.S. due to inadequate doses of solar ultraviolet-B radiation. Cancer. 2002 Mar 15;94(6):1867-75. 56. Grant WB. A multicountry ecologic study of risk and risk reduction factors for prostate cancer mortality. Eur Urol. 2004 Mar;45(3):271-9. 57. Banach-Petrosky W, Ouyang X, Gao H, et al. Vitamin D inhibits the formation of prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia in Nkx3.1;Pten mutant mice. Clin Cancer Res. 2006 Oct 1;12(19):5895-901. 58. Tokar EJ, Ancrile BB, Ablin RJ, Webber MM. Cholecalciferol (vitamin D3) and the retinoid N-(4-hydroxyphenyl)retinamide (4-HPR) are synergistic for chemoprevention of prostate cancer. J Exp Ther Oncol. 2006;5(4):323-33. 59. Gross C, Stamey T, Hancock S, Feldman D. Treatment of early recurrent prostate cancer with 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (calcitriol). J Urol. 1998 Jun;159(6):2035-9; discussion 2039-40. 60. Beer T, Lemmon D, Lowe B, Henner W. High-dose weekly oral calcitriol in patients with a rising PSA after prostatectomy or radiation for prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2003 Mar 1;97(5):1217–24. 61. Beer TM, Eilers KM, Garzotto M, et al. Weekly high-dose calcitriol and docetaxel in metastatic androgen-independent prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003 Jan 1;21(1):123-8. 62. Trump DL, Potter DM, Muindi J, Brufsky A, Johnson CS. Phase II trial of high-dose, intermittent calcitriol (1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3) and dexamethasone in androgen-independent prostate cancer. Cancer. 2006 May 15;106(10):2136-42. 63. Weitsman GE, Koren R, Zuck E, et al. Vitamin D sensitizes breast cancer cells to the action of H2O2: mitochondria as a convergence point in the death pathway. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005 Jul 15;39(2):266-78. 64. Welsh J. Vitamin D and breast cancer: insights from animal models. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004 Dec;80(6 Suppl):1721S-4S. 65. Christakos S. Vitamin D and breast cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1994;364:115-8. 66. Cui Y, Rohan TE. Vitamin D, calcium, and breast cancer risk: a review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006 Aug;15(8):1427-37. 67. Giovannucci E. The epidemiology of vitamin D and cancer incidence and mortality: a review (United States). Cancer Causes Control. 2005 Mar;16(2):83-95. 68. Vijayakumar S, Boerner PS, Mehta RR, et al. Clinical trials using chemopreventive vitamin d analogs in breast cancer. Cancer J. 2006 Nov;12(6):445-50. 69. Morishita M, Ohtsuru A, Kumagai A, et al. Vitamin D3 treatment for locally advanced thyroid cancer: a case report. Endocr J. 2005 Oct;52(5):613-6. 70. Lathers DM, Clark JI, Achille NJ, Young MR. Phase IB study of 25-hydroxyvitamin D(3) treatment to diminish suppressor cells in head and neck cancer patients. Hum Immunol. 2001 Nov;62(11):1282-93. 71. Witte KK, Nikitin NP, Parker AC, et al. The effect of micronutrient supplementation on quality-of-life and left ventricular function in elderly patients with chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2005 Nov;26(21):2238-44. 72. Schleithoff SS, Zittermann A, Tenderich G, et al. Vitamin D supplementation improves cytokine profiles in patients with congestive heart failure: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006 Apr;83(4):754-9. 73. Pittas AG, Harris SS, Stark PC, wson-Hughes B. The effects of calcium and vitamin D supplementation on blood glucose and markers of inflammation in non-diabetic adults. Diabetes Care. 2007 Feb 2. 74. Andjelkovic Z, Vojinovic J, Pejnovic N, et al. Disease modifying and immunomodulatory effects of high dose 1 alpha (OH) D3 in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1999 Jul;17(4):453-6. 75. Cantorna MT, Mahon BD. D-hormone and the immune system. J Rheumatol Suppl. 2005 Sep;76:11-20. 76. Pozzilli P, Manfrini S, Crino A, et al. Low levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in patients with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes. Horm Metab Res. 2005 Nov;37(11):680-3. 77. Anon. Vitamin D supplement in early childhood and risk for Type I (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. The EURODIAB Substudy 2 Study Group. Diabetologia. 1999 Jan;42(1):51-4. 78. Kiefer D. Unraveling a centuries-old mystery. Why is flu risk so much higher in the winter? Life Extension. February, 2007:22-8. 79. Lochner JD, Schneider DJ. The relationship between tuberculosis, vitamin D, potassium and AIDS. A message for South Africa? S Afr Med J. 1994 Feb;84(2):79-82. 80. Bellamy R, Ruwende C, Corrah T, et al. Tuberculosis and chronic hepatitis B virus infection in Africans and variation in the vitamin D receptor gene. J Infect Dis. 1999 Mar;179(3):721-4. 81. Nursyam EW, Amin Z, Rumende CM. The effect of vitamin D as supplementary treatment in patients with moderately advanced pulmonary tuberculous lesion. Acta Med Indones. 2006 Jan;38(1):3-5. 82. Schauber J, Dorschner RA, Coda AB, et al. Injury enhances TLR2 function and antimicrobial peptide expression through a vitamin D-dependent mechanism. J Clin Invest. 2007 Feb 8. 83. Available at: http://www.pdrhealth.com/drug_info/nmdrugprofiles/nutsupdrugs/vit_0265.shtml. Accessed March 1, 2007. 84. Meletis CD. Vitamin D. Cancer prevention and other new uses. Life Extension. March, 2006:50-58. 85. Vieth R. Vitamin D supplementation, 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations, and safety. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999 May;69(5):842-56. 86. Vieth R, Chan PC, MacFarlane GD. Efficacy and safety of vitamin D3 intake exceeding the lowest observed adverse effect level. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001 Feb;73(2):288-94. 87. Heaney RP, Davies KM, Chen TC, Holick MF, Barger-Lux MJ. Human serum 25-hydroxycholecalciferol response to extended oral dosing with cholecalciferol. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003 Jan;77(1):204-10. 88. Zeghoud F, Delaveyne R, Rehel P, et al. Vitamin D and pubertal maturation. Value and tolerance of vitamin D supplementation during the winter season. Arch Pediatr. 1995 Mar;2(3):221-6. 89. Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency: what a pain it is. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003 Dec;78(12):1457-9. 90. Adams JS, Fernandez M, Gacad MA, et al. Vitamin D metabolite-mediated hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria patients with. Blood. 1989 Jan;73(1):235-9. 91. Beer TM, Myrthue A. Calcitriol in the treatment of prostate cancer. Anticancer Res. 2006 Jul;26(4A):2647-51. 92. Tonner DR, Schlechte JA. Neurologic complications of thyroid and parathyroid disease. Med Clin North Am. 1993 Jan;77(1):251-63. 93. Grases F, Costa-Bauza A, Prieto RM. Renal lithiasis and nutrition. Nutr J. 2006;523. 94. Dumville JC, Miles JN, Porthouse J, et al. Can vitamin D supplementation prevent winter-time blues? A randomised trial among older women. J Nutr Health Aging. 2006 Mar;10(2):151-3. 95. Gloth FM, III, Alam W, Hollis B. Vitamin D vs broad spectrum phototherapy in the treatment of seasonal affective disorder. J Nutr Health Aging. 1999;3(1):5-7. 96. Lam RW, Levitt AJ, Levitan RD, et al. The Can-SAD study: a randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of light therapy and fluoxetine in patients with winter seasonal affective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2006 May;163(5):805-12. 97. Harris S, wson-Hughes B. Seasonal mood changes in 250 normal women. Psychiatry Res. 1993 Oct;49(1):77-87. 98. McGrath J, Saari K, Hakko H, et al. Vitamin D supplementation during the first year of life and risk of schizophrenia: a Finnish birth cohort study. Schizophr Res. 2004 Apr 1;67(2-3):237-45. 99. van Os J, Krabbendam L, Myin-Germeys I, Delespaul P. The schizophrenia envirome. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2005 Mar;18(2):141-5. 100. Kesby JP, Burne TH, McGrath JJ, Eyles DW. Developmental vitamin D deficiency alters MK 801-induced hyperlocomotion in the adult rat: An animal model of schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2006 Sep 15;60(6):591-6. |